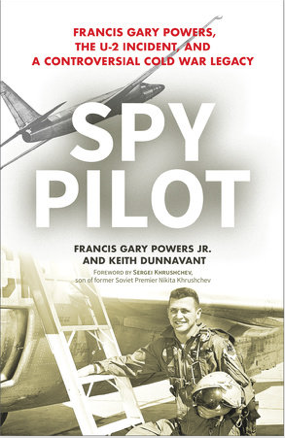

By Francis Gary Powers, Jr. and Keith Dunnavant

Reviewed by John Campbell, Lt Gen, USAF (Ret)

“Difficulties might arise out of these flights, but we can live with them”, that was how Allen Dulles, Director of Central Intelligence, made the case to President Dwight Eisenhower that the reward of authorizing a new reconnaissance program was worth any risk that came with it, uttering one of the classic understatements of the Cold War.

That program, was Project AQUATONE, its purpose to develop a new aircraft specifically designed to penetrate Russian airspace and ‘image’ high priority targets that were unreachable via existing platforms at the time, and to uncover evidence of a suspected Cold War “bomber gap.” The events surrounding the program are familiar to many of us of a certain age. Among them, the rapid development of a radically new aircraft, the U-2, by famed designer Kelly Johnson; the recruitment by the Central Intelligence Agency of a cadre of Air Force pilots, including Lieutenant Francis Gary Powers; the shoot down of Powers’ aircraft by a SA-2 missile deep over Russia in May 1960. That event resulted in the entrapment of President Eisenhower into an inept cover story by Soviet Premier Khrushchev; a show trial and then conviction of Powers on charges of espionage, for which he received a 10-year sentence; and the eventual exchange after 19 months, of Powers for Russian spy Colonel Rudolf Abel.

Probably less familiar to most, are the details of Powers’ life after his release. Although he was later found via multiple investigations to have acted honorably and within the spirit of the ambiguous direction he had been given, he was initially viewed with suspicion by the Air Force and CIA: after all, primarily because he had failed to use the built-in destruct device to destroy the plane if he was captured, he also had not committed suicide with a CIA-provided “poison pin”, and he had divulged more information during his trial than some thought fitting. Combined with some unfortunate and premature press coverage, that produced a stigma which followed him throughout the rest of his life. He was refused re-entry to the Air Force as he had been promised, spent a short time at CIA, and then worked as a Lockheed test pilot (where CIA paid his salary). After being released by Lockheed, he flew a traffic helicopter for a Los Angeles TV station until his death in a crash in 1977, leaving behind his wife, daughter and son, who also is the author of the book, Francis Gary Powers, Jr.

Spy Pilot is really two books. The first, written in the third person, recounts the familiar part of the story, from the inception of Project AQUATONE, to Powers’ repatriation and return to his family. Much of the story of the shoot down and prison experience has been told in more detail in Gary Powers own book, Operation Overflight; however, Powers, Jr. weaves in an interesting account of the Cold War environment and political backstory which add texture to the decisions surrounding the program. An interesting twist is the foreword by Sergei Khrushchev, son of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, in which he notes the differences in the ways Powers and Abel were treated after their exchange.

The second book is Powers, Jr.’s story. Changing to the first person, the author recounts his childhood years with his father and his recollections of his father’s growing cynicism about his shoddy treatment by the CIA and his continuing efforts to clear his name, including the publication of Operation Overflight, which he believed that the CIA used as pretext to have him fired by Lockheed. After Powers death in a helicopter crash in 1977, Powers, Jr. struggled with being the son of a man who many still regarded a traitor. He went through high school and college, alternately exploiting and avoiding his status as Gary Powers’ son. Finally coming to grips with his identity after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Powers Jr. began to dig deeper in to the story of his father’s experience.

And dig deep he did. He laboriously transcribed hundreds of hours of his father’s reel-to-reel tapes, reviewed his father’s prison journals and family correspondence, and submitted numerous Freedom of Information Act requests which produced previously classified records of his father’s debriefing and internal CIA reviews. He talked to family and friends, tracked down and interviewed senior government officers who had been involved in the program, corresponded with fellow Cold War historians and traveled to Russia to visit U-2 related sites.

Some of what he recounts is well known and helps to explain his father’s dilemma after his capture. The pilots involved in the program had received virtually no training to prepare for the possibility of capture and had been given no direction, or even discussion, on the use of the suicide devices they had been given. There was no discussion of a cover story and no apparent planning for the possibility that both plane and pilot might be captured. When the program seemed successful after a few months of being launched, complacency set in, to the point of Powers carrying his own wallet and personal documents with him on his first mission to fly completely over Russia.

Other information in the book is new, at least to the general public, and paints a picture of more bureaucratic inertia than intentional cover-up. Despite internal reviews which found no fault in Powers actions, no one in a position to do so wanted to publicly speak out on what had been one of the most highly-classified programs of its time—and had created one of the most embarrassing incidents of the Cold War. The author is candid about the difficulties of his father’s marriages, particularly to his first wife, whose alcohol dependence and erratic behavior raised concerns over the program’s security and led the CIA to screen the spouses of pilots who were involved in the follow-on A-12 OXCART program. In the end, the author notched some significant wins, including seeing his father receive the posthumous award of a Silver Star by the Air Force, designation of retired status as a Lieutenant Colonel and internment in Arlington cemetery. Most importantly, he was able to satisfy himself that his father had acted honorably.

This book comes across as a cathartic effort, not only to set the public record straight, but to let the author come to grips with his heritage and his obligation to protect his father’s legacy. It provides a huge amount of detail—perhaps too much for most readers—and is an inspirational case study in determination in dealing with government bureaucracy.

The U-2 is still flying today, and many forget that of its 54 years of service, only four—from first flight in August 1965 to Powers’ shoot down in May 1960, were “in the black”. Spy Pilot is the human side of that program and is a worthy addition to the record.

Spy Pilot earns a solid three out of four trench coats.

Lieutenant General John Campbell, USAF (Ret.) is a former Associate Director of Central Intelligence for Military Support.

Get more Under/Cover Book Reviews here....

And check out The Cipher Brief Book Store for more books by Cipher Brief Experts...

Interested in becoming a reviewer? Check out our Guidelines...