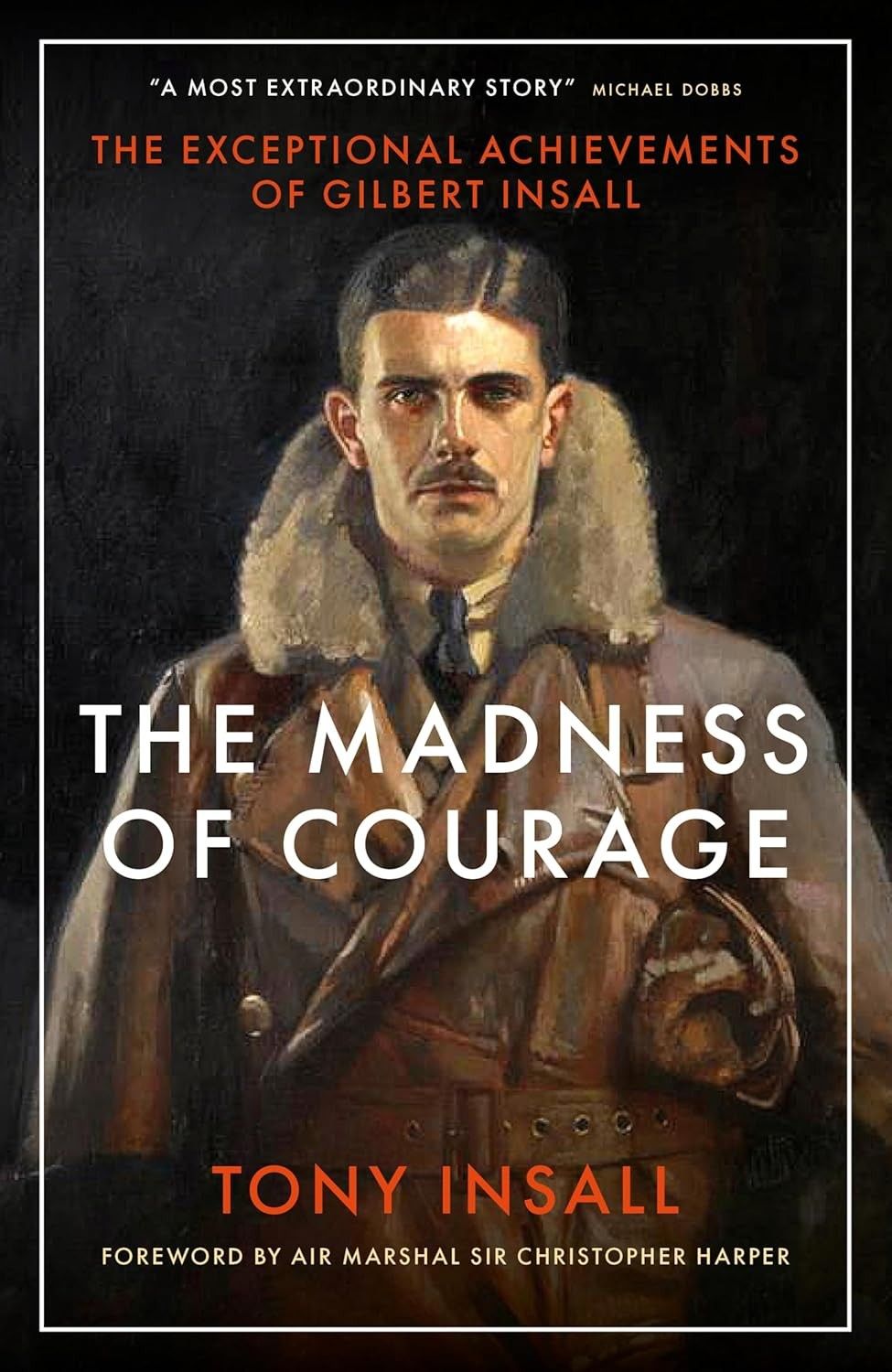

BOOK REVIEW: The Madness of Courage: The exceptional achievements of Gilbert Insall.

By: Tony Insall

Reviewed by: Tim Willasey-Wilsey

The Reviewer — Tim Willasey-Wilsey served for over 27 years in the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office and is now Visiting Professor of War Studies at King’s College, London. His first overseas posting was in Angola during the Cold War followed by Central America during the instability of the late 1980s. He was also involved in the transition to majority rule in South Africa and in the Israel/Palestine issue.

REVIEW — Is it more courageous to act heroically in a moment of extreme peril or to make a calm calculated decision to choose cold, hunger and danger in the slim hope of reaching safety and freedom? King George V believed that escape from a German prison camp required more courage than a brief moment of heroism fueled by the madness of courage.

Fortunately, this remarkable book Tony Insall, The Madness of Courage, tests this question against the only case of a man who both won the Victoria Cross and successfully escaped from a German prisoner of war camp during the First World War. That man was the author’s great uncle, Gilbert Insall. However, this is not a family history, still less a hagiography, and the author has searched beyond the family’s papers to find some remarkable documents in British and German archives.

The story also has historical significance. Gilbert Insall was one of three sons of a British dentist with a practice in Paris. As a young man he and his two brothers were fascinated by aviation and would cycle to an airfield near Versailles where Louis Blériot and the Farman brothers were experimenting with new aircraft designs. So, when war was declared in August 1914 the two older brothers travelled to England and joined the Royal Flying Corps.

Thanks to television replays of old films, we think we know a lot about wartime aviation. But with very few exceptions those films are about the Second World War and the remarkable aircraft such as the Spitfire, Hurricane and Mosquito. However, in 1914, military aviation was rudimentary. In the very early days, the casualties during training were astonishing. Gilbert was assigned to 11 Squadron which was equipped with the Vickers FB5 ‘Gunbus’. It was a “pusher” plane with the propeller behind the pilot and a Lewis gun mounted at the front. It could manage a mere 65mph and in high winds could even be propelled backwards and on occasions blown unintentionally behind German lines.

Everyone needs a good nightcap. Ours happens to come in the form of a M-F newsletter that provides the best way to unwind while staying up to speed on national security. (And this Nightcap promises no hangover or weight gain.) Sign up today.

Gilbert scored 11 Squadron’s first success in shooting down a German aircraft in September 1915 and two months afterwards came the incident when he earned the VC. He not only destroyed a second German aircraft but was himself forced down between the French and German trenches. With French assistance he worked overnight to repair his aircraft and took off in the early morning under a hail of enemy fire. He was both very brave and extremely lucky; two factors which often belong together.

Shortly thereafter, Insall was shot down and captured. So began nearly two years of captivity. Again, our knowledge of German prison camps and escapes is coloured by Second World War films like The Great Escape (1963), The Colditz Story (1955) and the Wooden Horse (1950). Many of the familiar actions in those films were influenced by developments in the 1914-18 war. Gilbert was involved in a tunnel escape from Heidelberg where the prisoners had to learn about hiding the spoil in the barracks’ eaves, making bellows to provide the tunnellers with fresh air and using planks from beds to shore up the tunnel roof.

There was also a more fundamental point. The duty to escape did not become the norm until the Second World War. In fact, there was more than a little suspicion at headquarters that some soldiers surrendered too easily and were all too willing to sit out the war in the relative comfort and safety of a German prison camp. There was a 3.04% chance of dying in a prison camp against a 12.9% chance of being killed in the trenches. Inside the camps there was also a feeling that “escape minded” inmates tended to bring additional German scrutiny and austerity to those who remained.

But perhaps the author’s greatest discovery was that the French (first) and then later the British developed a centralized escape organization. The British files were deliberately destroyed after the war but now we can see how MI9 (the Second Word War escape and evasion organization) developed its expertise so quickly after 1939, because much of the theory and practice had been devised from 1916 onwards. The author introduces us to Major John Snepp of MI1c in London and the charismatic Commandant K in Paris.

Are you Subscribed to The Cipher Brief’s Digital Channel on YouTube? Watch expert-level discussions on The Middle East, Russia, China and the other top stories dominating the headlines.

Another revelation was how much intelligence the Germans obtained from captured British airmen who were often lulled into a false sense of security by German hospitality and a tenuous narrative that German and British aviators shared a code of knightly conduct. Later in the war pilots were warned not to fall for such stratagems.

Until Snepp’s organization was up and running, it was up to the prisoners’ families to provide assistance. Gilbert Insall’s father and brothers in Paris showed amazing inventiveness and tenacity. One suspects that the dentist’s fine motor skills must have helped when they hid maps inside a hollowed out set of dominoes and then used lead to ensure that the weight of each piece felt correct. Gilbert and his family employed lemon juice and milk as secret inks which were far too easy to detect but, fortunately, they used them on the insides of envelopes which the Germans seem not to have checked. (Later the British secret service would recommend BS (bird shit) and semen to agents who had run out of specialized ink).

Gilbert’s tunnel escape from Heidelberg failed as did his sudden opportunistic escape from Crefeld in the back of a horse-drawn van. On both occasions it was the inability to find shelter which undermined his efforts. But his third attempt in September 1917 succeeded and with two colleagues he crossed the Dutch border after 21 months in captivity. His celebration was sufficiently bibulous to earn an official complaint to go with his VC.

The Cipher Brief participates in the Amazon Affiliate program and may make a small commission from purchases made via links.

Interested in submitting a book review? Send an email to Editor@thecipherbrief.com with your idea.

Sign up for our free Undercover newsletter to make sure you stay on top of all of the new releases and expert reviews.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business.