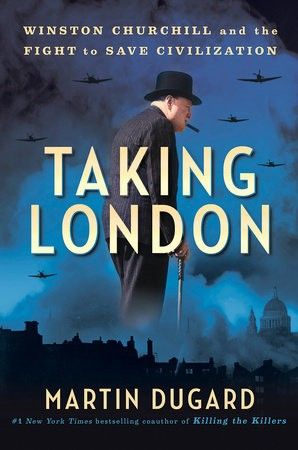

BOOK REVIEW: TAKING LONDON: Winston Churchill and the Fight to Save Civilization

By Martin Dugard / Dutton (On sale: June 11)

Reviewed by: Nick Fishwick

The Reviewer — — Nick Fishwick CMG retired after nearly thirty years in the British Foreign Service. His postings included Lagos, Istanbul and Kabul. His responsibilities in London included director of security and, after returning from Afghanistan in 2007, he served as director for counter-terrorism. His final role was as director general for international operations.

REVIEW — I am old enough to remember Winston Churchill’s funeral. It was a cold January day and my parents, their four children and random droppers-in were crowded around our tiny TV set, watching the pictures in black and white.

It was the closest I have ever seen my father to tears, which was not very close. For most British people of my parents’ generation, born in the early 1930s, nothing would ever approach the impact of listening to Churchill’s growling, lisping, perhaps slightly tipsy defiance of Nazi Germany in Parliament and on BBC radio in 1940. “Fight them on the beaches;” “this was their finest hour;” “never was so much owed by so many to so few:” words roared out by this old British lion. At perhaps the darkest period in modern British history, he showed a genius with language that inspired the nation, whether kids like my father, men and women in uniform, or defeatist members of parliament. This is the Churchill celebrated in Mr. Dugard’s book, TAKING LONDON: Winston Churchill and the Fight to Save Civilization.

It is perhaps not an original depiction of the great statesman, but perhaps like a vintage Spitfire, this Churchill is all the better for the occasional outing. Dugard tells a gripping story of how Churchill led Britain through the crisis between his becoming Prime Minister, in May 1940, and British victory in the Battle of Britain four months later.

To keep the pace of the narrative fast and dramatic, Dugard favors very short sentences and is economical with his verbs. “Winston has had an auspicious day. An auspicious week, actually. And now he is one phone call away from its crowning moment,” begins one chapter. “The British like Hitler. A lot,” two sentence/paragraphs tell us of Britain in the 1930s. (I know which “British” he means, but actually most British people always disliked Hitler, a lot.) The language occasionally drops into journalese cliches like (sad for Shakespeare) “there’s the rub” and that someone was “affable.” But undoubtedly the story jogs along.

And there are some smart touches. Using the US ambassador Joseph Kennedy as a bad-guy is an effective contrast to the heroic description of Churchill and gives some flavor of the US-UK relationship’s complexities. Dugard focuses on other personalities to make the reality of the Battle of Britain come alive. One of his most notable heroes is Flight Lieutenant Peter Townsend (at one point referred to as Pete Townsend, as if he also played guitar for The Who,) best known to Brits as the man who almost married our late queen’s younger sister. Dugard’s eye-watering descriptions of Townsend’s courage and patriotism left me thinking we should have let him have Buckingham Palace.

Other heroes get their fifteen minutes or more. Sir Hugh Dowding showed guts and strategic foresight in organizing the British air force’s successful resistance. Ed Murrow, the young American correspondent in London and a great symbol of the special relationship, braved the Germans’ pummeling of London to send admiring descriptions of Britain’s refusal to bend. He politely wished his audience “good night, and good luck” at the end of every broadcast. R.J. Mitchell, designer of the Spitfire, who died young two years before the war even started. And countless fighter pilots, including the odd eccentric American, who offered themselves up against the German onslaught.

Above all, Dugard’s achievement is to give a vivid sense of what it was like to fight, even die, in a fighter plane in 1940, careering around the skies at 300 mph with guns blazing away, engines catching fire, wings blown off, escape hatches jammed: and if you survived one of these encounters, off you went to the next one in a few hours time. Dugard’s accounts of the Battle of Britain, on the ground – the bases, the pubs near the bases, the hospitals – and in the air are transfixing. I would have complete confidence in the accuracy of Dugard’s descriptions of the fighter planes, how they worked, what they fired, and of how Britain’s defense was organized.

Perhaps I would have slightly less confidence in other aspects of his history. Let us go back to Churchill. It is true that Churchill was a genius in inspiring his country in 1940. From Dugard’s account, the reader will wonder how on earth Churchill was not the country’s leader long before 1940. The answer is that his career had been marked by failure and controversy. The disastrous Gallipoli campaign in the First World War had been his pet project. Then he championed the White Russians in their unwinnable fight against the Bolsheviks. As chancellor (finance minister) in the 1920s he devastated the British economy by going back on the gold standard and forced cuts in British defense spending. In the 1930s he opposed moves towards Indian self-government; he loudly supported Edward VIII, later known for his pro-Nazi leanings. Feminist activists could not forget his opposition to Suffragettes, militants who wanted the vote extended to women. The Labour Movement generally despised him. So, by the time Churchill started warning about Hitler many people thought: “he has been wrong about everything else, so he must be wrong about this.”

Dugard also brushes over the reality of how Churchill finally got to the top. What finished Neville Chamberlain’s in May 1940 was the failure of Britain’s intervention in Norway, a shambolic affair for which Churchill, as naval minister (First Lord of the Admiralty), was principally responsible. In the grand scheme of things, it was as well that this responsibility was overlooked: Britain in 1940 needed someone who relished the struggle, not a highly intelligent, boring administrator like Chamberlain. Still, it’s funny how things turn out.

The Cipher Brief participates in the Amazon Affiliate program and may make a small commission from purchases made via links.

Interested in submitting a book review? Send an email to Editor@thecipherbrief.com with your idea.

Sign up for our free Undercover newsletter to make sure you stay on top of all of the new releases and expert reviews.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business.