Reviewed by James L. Bullock

It is an oft-told tale in Foreign Service circles that America’s diplomats, not its soldiers and sailors, are the nation’s first line of defense. Certainly more U.S. ambassadors than generals or admirals have been killed in the line of duty since World War II. That fact, however, does little to redress the enormous mismatch of bureaucratic and budgetary clout between our career diplomatic and development civilians, on the one hand, and their military counterparts, on the other.

There are many reasons for this imbalance, of course, but public sentiment plays a part: many more Americans have served in the military or know someone who has served, and DoD’s ubiquitous recruiting stations are supported by sophisticated media advertising that reaches into every home. That is not the case with America’s much smaller diplomatic service.

Department of State recruiting is relatively low-key, generally more selective, and its domestic spending is largely unseen. The elitist stereotype of “male, pale and Yale” was still a reasonably accurate – if far from appealing to most - description of a typical Foreign Service Officer (FSO) through the 1970s.

That is when a class action suit against the State Department on behalf of its female employees - “The Palmer Case” – led to more “female-friendly” entrance criteria, evaluation and promotion policies, and assignments processes throughout the Foreign Service. These changes were later incorporated into The Foreign Service Act of 1980, which mandated a diplomatic service “truly representative of the American people throughout all levels of the Foreign Service.”

Ambassador Prudence Bushnell’s account in this book of her own experience entering, and then rising through the ranks of the Foreign Service exemplifies the challenges faced by women and minorities of that first “post-Palmer” generation trying to break into a traditional, and still “pale male” - dominated club.

As this was happening, the very nature of diplomatic service was changing. New communication technologies brought both an American media spotlight and Washington oversight much closer to the field as political violence directed at relatively soft diplomatic targets was increasing. After 9/11, U.S. diplomats were asked more frequently to serve at high-priority “danger” posts, alongside or embedded within U.S. military units, and without their families. Such “unaccompanied” hardship assignments were rare pre-9/11, but they soon became both desirable and essential for an FSO’s career advancement.

Foreign Service “culture” changed as military practices and procedures were imposed, and much has been written about the “militarization of American diplomacy” that has resulted. The number and status of diplomatic security agents – many with pre-Foreign Service experience in the military – also grew over this period in a parallel development.

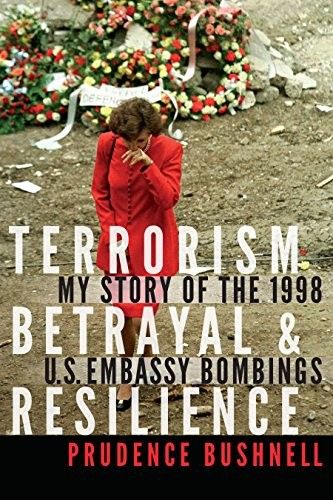

All this cultural change, evolving as Ambassador Bushnell was pursuing her diplomatic career, is the context for her book, Terrorism, Betrayal & Resilience: My Story of the 1998 U.S. Embassy Bombings. In a real sense, it is her personal “cri de cœur” for respect, as a diplomat, as a civilian and as a woman. The 1998 bombing may have been the initial catalyst for her book, but the result touches on much more.

Prudence – “Pru” - Bushnell came from a Foreign Service family, and her first impressions were as a “third country kid” growing up in Germany, France, Pakistan and Iran. Her childhood recollections, in the opening section of the book, help the reader to understand how this “kickass woman” - as Bushnell likes to describe herself – came to be the American Ambassador in Nairobi in 1998, when Al-Qaida operatives used an explosives-laden truck to blow up the Embassy, killing hundreds of people and wounding thousands more.

Bushnell’s book is not an academic study, and it is not a dispassionate after-action report. The author is anything but dispassionate. In many ways, it reads like a diary, filled with personal reactions and private reflections on what it means to be a leader in a crisis. In retelling her own story, she overlays a time line of major security-related incidents being reported in the media, linking them to the political environment in Washington that she was trying to influence.

She quotes, more than once, from an annual performance evaluation that criticized her for “overloading the circuits” in her zeal to get resources, specifically security enhancements, for her mission. For that, she makes no apology – again and again, she gives examples of how she strove not just “to do things right,” but “to do the right thing.” In explaining herself and justifying her assertive behavior, she frequently draws on her pre-Foreign Service experience as a human resources consultant, later reinforced during domestic State Department assignments as a leadership trainer at the Foreign Service Institute. As a self-described “diminutive female,” she repeatedly relates how she was determined not to be pushed around. Sometimes, as she tells it, that helped her, and sometimes it got her into trouble.

This book is part of the “Diplomats and Diplomacy” series published jointly by the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training (ADST) and DACOR, a private organization originally known as “Diplomats and Consular Officers Retired,” through Potomac Books, an imprint service of the University of Nebraska Press. Most of the books in this extensive series are based on oral histories initially recorded by ADST and later transcribed and deposited at the Library of Congress. Some of these histories are later expanded for publication in book form. The stated purpose of the series is “to increase public knowledge and appreciation of the professionalism of American diplomats and their involvement in world history.”

Ambassador Bushnell’s narrative is divided into three sections: “What Happened?” – with its graphic descriptions of the actual bombing and its immediate aftermath, “How Did It Happen?” - with its critical review of the U.S. Government’s anti-terrorism response from the 1980s onward, and a detailed description of recurring bureaucratic failures, and “So What?” – a summary of her leadership lessons and a plea from retirement for the next generation to correct the shortcomings that allowed the 1998 bombing, and others that followed, to happen.

Clearly, Ambassador Bushnell wants to put her personal stamp on the history of the August 1998 bombing of the U.S. Embassy in Nairobi. Her sensitive account is full of fascinating personal detail that will be of particular interest to the reader seeking to understand what it is really like to serve as a U.S. diplomat in these transitional times.

From 1-4 trench coats:

This book earns a rating of 3.5 trench coats.

James L. Bullock is a retired senior Foreign Service Officer, with over forty years of U.S. Government experience, principally serving as a State Department diplomat at Arabic-speaking posts.

Terrorism, Betrayal & Resilience: My Story of the 1998 U.S. Embassy Bombings, by Ambassador Prudence Bushnell, Potomac Books, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2018