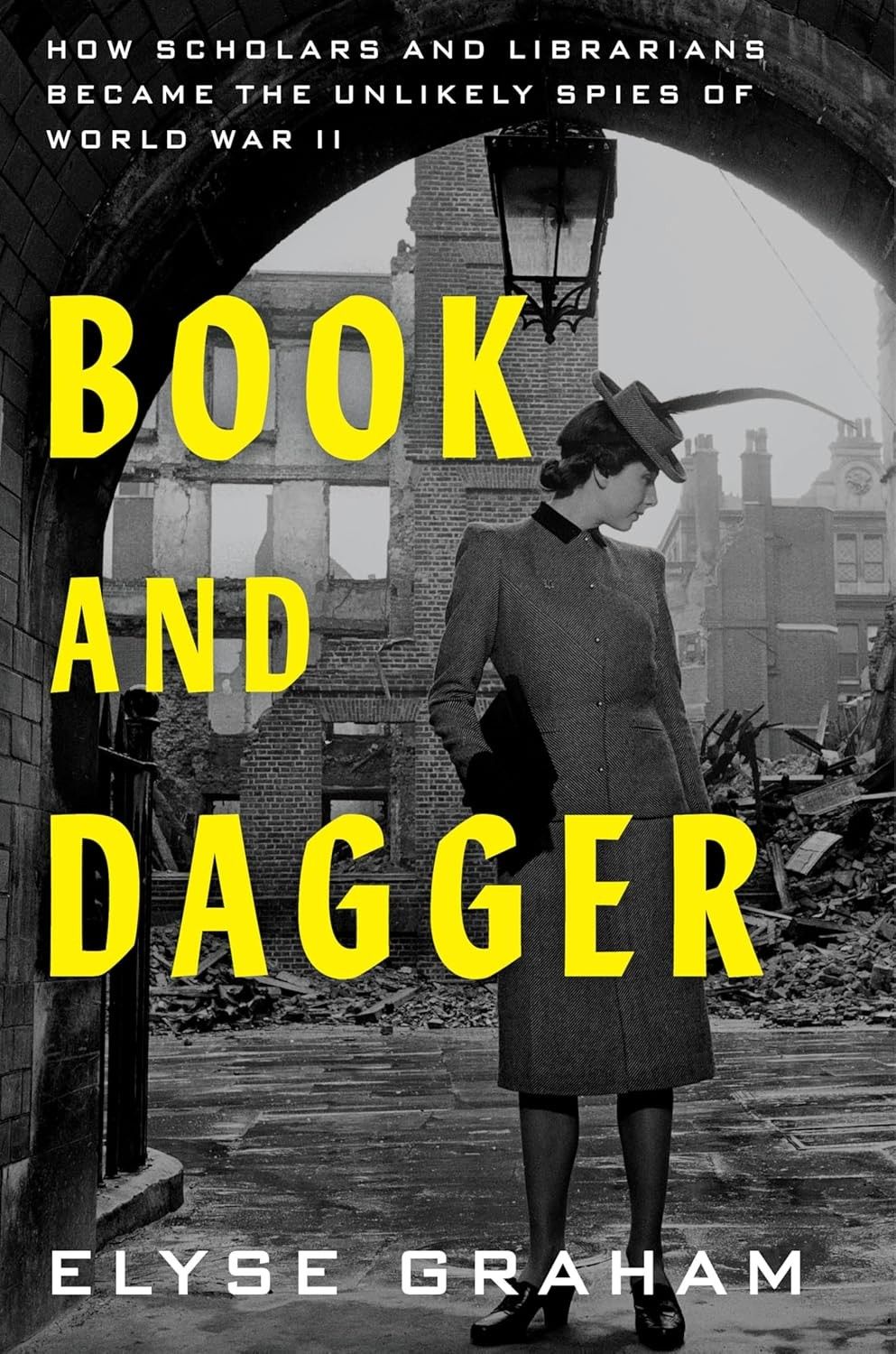

BOOK REVIEW: BOOK AND DAGGER, HOW SCHOLARS AND LIBRARIANS BECAME THE UNLIKELY SPIES OF WORLD WAR II

By Elyse Graham/Ecco

Reviewed by: Nicholas E. Reynolds

The Reviewer — Nicholas Reynolds, served in the U.S. Marine Corps as an infantry officer and historian and later had a career with the Central Intelligence Agency as an operations officer and historian for the CIA Museum. He has a PhD from Oxford University and is the author of Need to Know, World War II and the Rise of American Intelligence (Mariner, 2022), a New Yorker “Best of 2022” selection. More detail on his writing and background can be found on his website.

REVIEW — Elyse Graham, professor of history at Stony Brook University, writes about the American academics who left the halls of the Ivy League to fight World War II. Her basic argument is that, unconstrained by precedent, they were able to make an appreciable difference. “The world was incredibly fortunate that the United States was able to turn its greatest disadvantage, the lack of a standing intelligence service, into its greatest advantage. … Because they weren’t tied down by established ways of doing things, the professors and librarians…and the refugees who joined them were able to create something new” and vibrant. With their academic training, they were ready-made intelligence officers: “These scholars weren’t amateurs in intelligence. They were experts in intelligence. It’s just that the intelligence world didn’t know it yet.”

Most of those academics found their way into the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), whose director William J. Donovan allegedly prized PhDs who could win a bar fight. If there is one hero who stands out in Book and Dagger, it is Sherman Kent, the Yale historian who was one of the founders of Donovan’s Research and Analysis Branch (R&A) and, almost singlehandedly, of modern intelligence analysis. Graham brings Professor Kent to life with his red suspenders, chewing tobacco, and foul language, not to mention his skill at firing bits of chalk into the open mouths of snoring students. Building on the twin foundations of his training as a historian and his wartime experience, Kent went on to a distinguished career as an intelligence officer after the war.

Other characters in the book are less well known. Graham highlights Adele Kibre, an accomplished mediaevalist and diligent researcher who collected open source material for OSS in Scandinavia during the war. In this book she emerges “quite quietly and unexpectedly, [as] the Allies’ greatest agent.” Another character was more like the exception that proves the rule. Harvard anthropologist Carleton Coon didn’t wait for the war to get out of the stacks. Even before Pearl Harbor, he was roaming the back country in North Africa, hoping to become Lawrence of Morocco. In 1942 and 1943, he was on the OSS payroll, teaming up with British saboteurs to train guerrillas, and then conducting his own decidedly odd operations. Today he is remembered more for his racist theories than for helping to establish a new profession.

While interesting and well-written, a chapter-long sidebar on Operation Mincemeat and D-day comes across as barely relevant to the other themes in Book and Dagger.

Subscriber+Members have a higher level of access to Cipher Brief Expert Perspectives and get exclusive access to The Dead Drop, the best national security gossip publication, if we do say so ourselves. Find out what you’re missing. Upgrade your access to Subscriber+ now.

Old-school intel scholars will dispute some of Graham’s findings. Kibre did admirable work but does not appear on any other list of the war’s greatest agents. She was not like Fritz Kolbe, a German bureaucrat who risked his life to deliver bags of secret Nazi documents to OSS, or the Soviet spy Richard Sorge who reported strategic secrets from Tokyo and paid with his life. Similarly, the author generally inflates the importance of OSS reporting. Recent studies have shown that American decision-makers paid much less attention to OSS products than to the results of codebreaking. Hands down the generals’ favorite reading was not R&A’s “The War This Week” but the War Department’s top secret, very close-hold “Magic Summary” of information gleaned from intercepts. That said, few would dispute Graham’s conclusion that we are indebted to Kent and his colleagues for founding a new profession.

This book is hard to categorize, falling somewhere in between a commercial and an academic work. It is not exactly an update of Barry Katz’s groundbreaking Foreign Intelligence, Research and Analysis in the Office of Strategic Services (Harvard, 1989), long the go-to book on the subject. It is closer to cultural historian Kathy Peiss’s Information Hunters, When Librarians, Soldiers, and Spies banded together in World War II Europe (Oxford, 2019), which focuses on the collection of printed matter in Europe and how it was harnessed to produce intelligence.

Graham is an academic and does show us how she arrived at her sums. The 53 pages of endnotes point to sources and interesting facts not in the text, even if one set of records is largely absent: the voluminous files at the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland, especially Record Group 226 (OSS). Book and Dagger has some things in common with creative nonfiction. With her lively prose, Graham fills in gaps in the records. In a book about intelligence it is not unusual to fall back on collateral sources; if we don’t know what Jones did in a crisis, we look at what Smith did. But, as the author openly admits, she goes a step further: some of her prose is extrapolated from the facts, which is less usual, and may give some readers pause. She writes: “For the sake of continuity, I have included occasional imagined scenes in this book, which are always clearly indicated.”

Read and enjoy the book. Appreciate the apt characterizations, especially of Sherman Kent and historians as intel officers. But remember that not everyone will agree with some of Graham’s methods or all of her conclusions.

The Cipher Brief participates in the Amazon Affiliate program and may make a small commission from purchases made via links.

Interested in submitting a book review? Send an email to Editor@thecipherbrief.com with your idea.

Sign up for our free Undercover newsletter to make sure you stay on top of all of the new releases and expert reviews.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business.