BOOK REVIEW: Apocalypse Television: How The Day After Helped End the Cold War

By David Craig /Applause Theater and Cinema Books

Reviewed by John A. Lauder

The Reviewer – John A. Lauder is a Senior Fellow at the Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control and is a founder of the James A. Garfield Center for Public Leadership at Hiram College. He retired from the US government with over 33 years of managerial, analytical, and policy experience in the Central Intelligence Agency, National Reconnaissance Office, and as an arms control negotiator. He has continued to lead efforts to improve intelligence on weapons of mass destruction and to facilitate verification of international agreements.

Review: The Day After, a made for TV movie that appeared on ABC in November 1983 at the height of the Cold War, may have had the single greatest influence on how the American public then viewed the consequences of nuclear war. The film was watched by an estimated 100 million Americans – the largest audience for a TV movie in history -- and was said to have influenced President Ronald Reagan’s decision to pursue arms control. The film was subsequently screened elsewhere in the world, even in the Soviet Union in 1987. Some one billion persons may have eventually seen the movie.

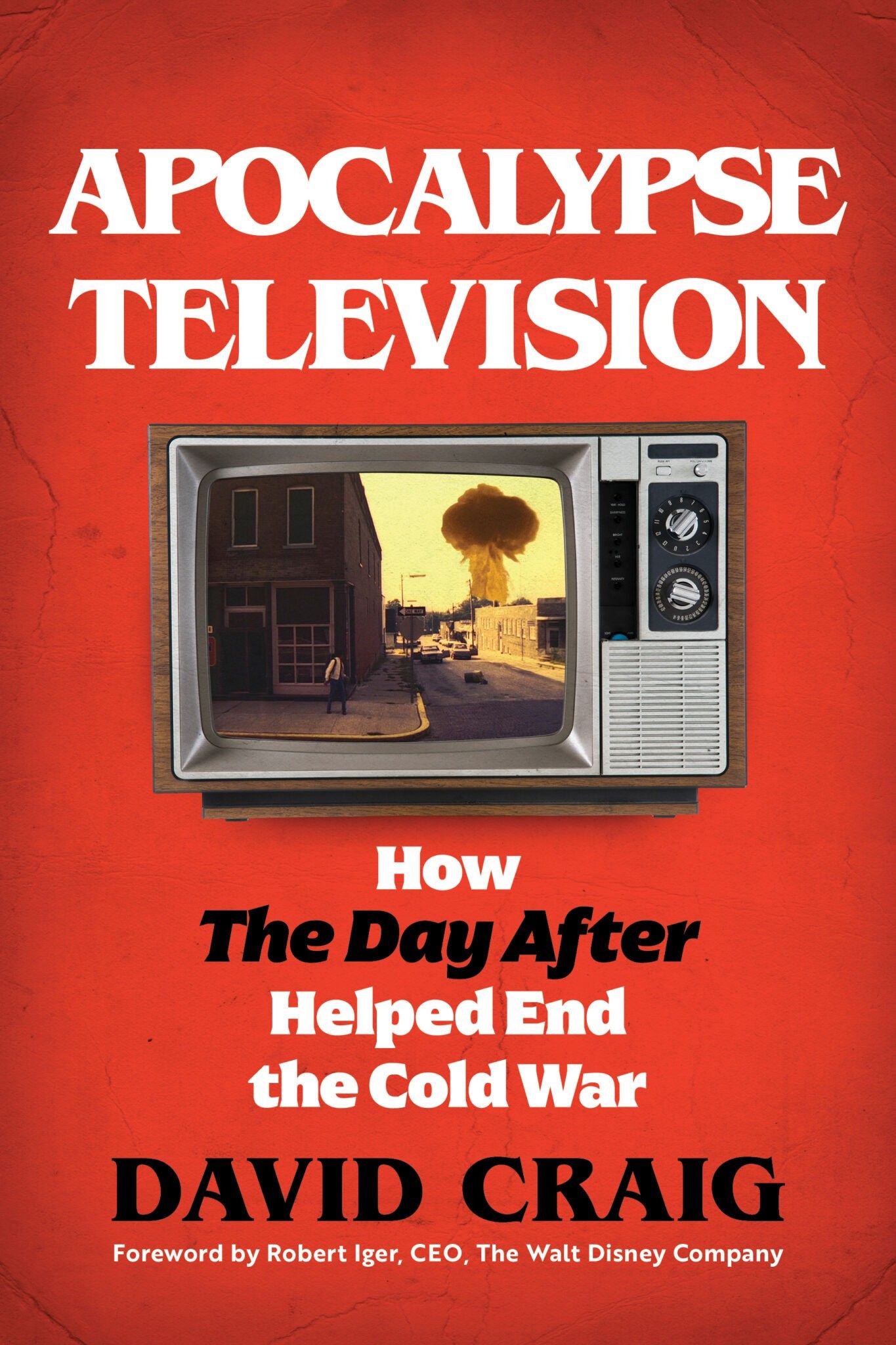

Apocalypse Television: How The Day After Helped End the Cold War by David Craig, a former media executive and now a leading scholar of “creator culture,” tells the story of how the movie came to be made and the controversies surrounding its depiction of nuclear war in the American heartland. The book was timed to appear on the 40th anniversary of the broadcast of the movie. Robert Iger, CEO of The Walt Disney entertainment conglomerate and an ABC veteran himself, sets the tone in his foreword to the book with the phrase “those who tell the stories may save the world.”

Apocalypse Television is not at first glance a book that would be high on the reading list of most readers of The Cipher Brief. Much of the book is inside-baseball on how broadcasting decisions were made in the golden age of network television. The author weaves a fascinating story of that milieu and how it led to The Day After. It is a nostalgic look at an era that the proliferation of cable and streaming networks has ended.

There are also intriguing personalities. The book is dedicated to Brandon Stoddard, the head of ABC’s movie division when The Day After was produced and a later member of the Television Academy’s Hall of Fame. Stoddard was known as the father of the miniseries and helped bring to the screen such consciousness-raising shows as Roots. Through his own force of personality and skill in broadcasting, Stoddard brought The Day After to audiences despite political controversy, an initial lack of sponsors, and even death threats.

In creating The Day After, Stoddard was surrounded by a team of talented, strong-willed, and at times bickering producers, directors, editors, and writers. Craig quips: “The creative team responsible for making The Day After readslike a classic joke. What happens when you combine a man with a Pharaoh complex, a child of vaudevillians, the manager of the Grateful Dead, a second generation Armenian, and a dinner guest of J. Robert Oppenheimer? A television movie about the end of the world.”

The movie is mostly set in and around Lawrence, Kansas and Kansas City, Missouri, including farms, a hospital, a college campus, and nearby Minuteman missile silos. The plot follows several individuals and families as they lead their daily lives with the backdrop of a developing crisis between NATO and the Warsaw Pact over Berlin. The crisis escalates rapidly to conventional conflict, to the use of nuclear weapons in Europe, and then to full-scale intercontinental nuclear war. Some of the most dramatic scenes in the movie are as the characters watch Minutemen missiles being launched, arching into the sky over fields, homes, the hospital, and a packed stadium.

An airman guarding the silos sums up the scene and the thoughts of all those watching the launching missiles: “You know what this means don’t you. Either we fired first and they’re going to try to hit what’s left. Or they fired first, and we just got our missiles out of the ground in time. Either way, we’re going to get hit.”

The Soviet missiles soon do hit and the movie depicts five minutes of gruesome destruction. In the aftermath of the destruction as power, fuel, and food dwindle away, the survivors succumb to starvation, lawless violence, and radiation poisoning.

Craig quotes renowned movie critic Roger Ebert who wrote that the most jarring part of the movie is that there was no Hollywood ending. The movie “says that a worldwide nuclear war would be so devastating that not even an ABC TV docudrama with Jason Robards can find a way to haul the story around to an ending you will be able to live with and sleep on.”

Even before its broadcast, leaked copies of the movie were exploited by both the left and the right to advance their own views of nuclear conflict. Disarmament advocates used the movie to bolster their call for a freeze on nuclear weapons while some in the Christian Right saw the “bright side” of nuclear war as a necessary step leading to the Last Judgment. Others claimed that the movie demonstrated the need for the President’s Strategic Defense Initiative. The Administration – with David Gergen at point – rolled out a host of spokespersons to try to take control of the narrative to demonstrate the wisdom of President Reagan’s policies of strengthening the weapons of deterrence.

To debate such issues and perhaps to calm the country after the wrenching spectacle of hopeless destruction, ABC moderator Ted Koppel hosted a remarkable 90-minute special edition of Viewpoint immediately following the showing of the movie. Guests included George Schultz, Henry Kissinger, Robert McNamara, William Buckley, Brent Scowcroft, Elie Wiesel, and Carl Sagan.

Apocalypse Television is disappointing in capturing the full national security context of these debates and in fulfilling the promise of its subtitle – How the Day After Helped End the Cold War. Understandingly, David Craig is more at home with the personalities and folk lore of network TV than he is with the arcane history and strategy of the Cold War. He sometimes falls back on short-hand tropes such as “miliary industrial complex” rather than illuminating the substance of the effort to maintain deterrence while lowering force levels and reducing the possibility of fatal misunderstandings.

Subscriber+Members have a higher level of access to Cipher Brief Expert Perspectives and get exclusive access to The Dead Drop, the best national security gossip publication, if we do say so ourselves. Find out what you’re missing. Upgrade your access to Subscriber+ now.

In any case, assessing the ultimate impact of the movie would have been a heavy lift as historians differ on the factors that ultimately led to the end of the Cold War. Key contributing factors were the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union, but the book makes little effort to assess whether The Day After had significant impact east of the Elbe. The Day After was not viewed in the Soviet Union until 1987 and its viewing was as much a symptom of the changes underway rather than a cause.

The book misses the context of the mass demonstrations that were underway to protest the deployment of Pershing II ballistic missiles and ground-launched cruise missiles in Europe in the same fall as the airing of the movie. Those deployments were part of a dual track strategy devised by NATO to counter the Soviet deployment of the intermediate-range SS-20 by bolstering NATO’s theater nuclear delivery systems but also pursuing negotiations with the Soviet Union on such systems. The success of that policy ultimately led in 1987 to the Treaty on Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF), which required the elimination of an entire class of weaponry and led to even more sweeping arms control reductions and monitoring measures.

The book does make a case though that the showing of the movie contributed to a tonal shift in US rhetoric and policy toward the Soviet Union that may have facilitated the conclusion of the INF Treaty and to a series of summits and negotiations that gave birth to the sweeping arms control agreements that helped manage the end of the Cold War. The author is understandably cautious in assessing the impact of the movie on President Ronald Reagan compared to other factors leading to the tonal shift. Craig notes “No one would claim that The Day After singularly changed the President’s mind.”

Still, “film occupied the President’s attention like no other medium… and the President was as likely to learn about foreign policy from a Hollywood feature than from his own foreign policy advisers.” Reagan had screened the movie a month before its network broadcast. Three weeks or so after that screening, the President received an update on the Single Integrated Operational Plan or SIOP (the US contingency plans for nuclear war), which he viewed in part through the lens of the movie that he had seen. The book quotes Reagan’s diary entry about the SIOP briefing, which he described as “a most sobering experience . . . In several ways the sequence of events parallels those in the ABC movie . . . simply put it was a scenario . . .that could lead to the end of civilization as we know it.”

It would have been insightful had the book explored in greater detail the reactions of other key policy players to the film and how the viewing might have led to their subsequent actions. George Herbert Walker Bush as Vice President was part of the planning for how the Administration would react to the movie and Brent Scowcroft was one of the panelists in the Ted Koppel Viewpoint special following the broadcast of the film. Years later now President H.W. Bush, with Scowcroft as his national security adviser, would shape the high-water mark of arms control and nuclear de-escalation between Washington and Moscow. George Schultz and Henry Kissinger were also Koppel panelists and would go on years later to advocate for a world free of nuclear weapons. Some other author will have to answer the question of whether the experience of all four of them with The Day After influenced the evolution of their own approaches to the prevention of nuclear conflict.

Those hopes for a world free of nuclear weapons are sliding into a distant future and nuclear saber-rattling is again the norm, especially from Putin’s Russia. The agreements that helped manage the end of the Cold War are nearly all defunct. Those of us who have been involved in the intensifying discussion of the future of deterrence and arms control in this new nuclear age have heard the lament that the American public no longer has a deep understanding of the destructive power of nuclear weapons and the existential threat of a full-scale nuclear war. Craig ends his book by acknowledging “the rising chorus for a Twenty-first Century version of The Day After”. Perhaps Apocalypse Television will inform and inspire such an effort.

The Cipher Brief participates in the Amazon Affiliate program and may make a small commission from purchases made via links.

Interested in submitting a book review? Send an email to Editor@thecipherbrief.com with your idea.

Sign up for our free Undercover newsletter to make sure you stay on top of all of the new releases and expert reviews.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business.