Letters from a Private Spy Reveal a Complicated Life

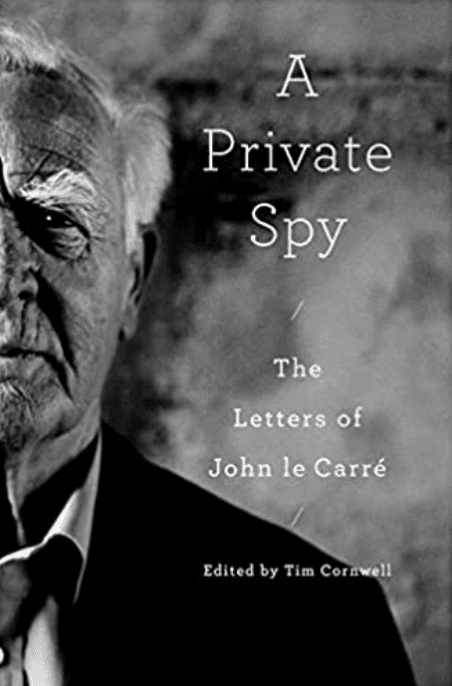

BOOK REVIEW: A Private Spy: The Letters of John le Carre

Edited by Tim Cornwell / Viking

Reviewed by Nick Fishwick

The Reviewer – Former Senior Member of the British Foreign Office Nick Fishwick CMG retired after nearly thirty years in the British Foreign Service. His postings included Lagos, Istanbul and Kabul. His responsibilities in London included director of security and, after returning from Afghanistan in 2007, he served as director for counter-terrorism. His final role was as director general for international operations.

REVIEW — “No number of ‘sorry’s’ can wipe away my disloyalties”. So wrote John le Carre, real name David Cornwell, to his wife in his early seventies. He was referring to his frequent sexual infidelities – a starker word than “disloyalties” – rather than to betrayal of cause or country. Few writers have dwelt more on the complexities of disloyalty, including the exploitation of it, than le Carre.

From the early 1960s, when he was a young MI6 officer, he published well over twenty novels, many of which looked at espionage in a way that no other writer had done. This brilliantly entertaining collection of letters, edited by le Carre’s son, who died shortly before A Private Spy was published, gives some insights into what was going through the writer’s mind when the books were being written.

As le Carre was himself happy to admit, he lived one hell of a life.

He came from an unstable background: abandoned by his mother at the age of five, and his father was a confidence trickster and fraud on a massive and serial scale. Le Carre went to the inevitable boarding school and after national service, Oxford, a spell as a ski racer and as a teacher at Eton, he joined MI5 and then MI6. The combination of being “blown” by the MI6 traitor George Blake and the success of his writing career, which translated well to big and small screens, led him to concentrate on the life of a writer. This is a choice for which readers (and doubtless, MI6) are grateful.

The correspondents in the book are testimony to the richness and variety of his life – letters to writers like Graham Greene, William Burroughs, Tom Stoppard, Philip Roth and Ian McEwan; to British diplomats, British spies, German spies, Russian spies (sadly no obvious American spies); to actors from Sir Alex Guinness to Gary Oldman; to human rights activists, journalists and to the odd curious member of the general public; and many letters to his family, which show an honesty and compassion that add a dimension to his own complex character.

The richness of his life is also demonstrated in other ways – he made a lot of money from his work and spent a lot of time travelling to some pretty agreeable locations. He was not so short of vanity to refuse awards (only those that were offered by the British government) or to show understandable pride at the sales and film adaptations that his writing spawned (though he was generous in giving the real credit to actors, publishers, script writers and directors).

But what did he believe, and where were his own loyalties?

Like a lot of Englishmen of his background, le Carre struggled with patriotism and a form of English identity defined by the governing classes – the Empire, the Church of England, the boarding school system, etc. Without making too vulgar comparisons, you can’t help noting that this was the same struggle that the classic British traitors Philby, Blunt, Burgess and Maclean had gone through.

Not that le Carre had any time for the traitors: he had nothing but contempt for Kim Philby, and refused to meet him, noting that his only interest in doing so would have been “zoological”. But le Carre’s comments on his country are those of a maddened and sometimes thwarted lover, disapproving of the company the other person keeps. Sometimes he seems more comfortable with modern-day Germany, noting that it “is aware of its past, and keen to correct it. Britain? Forget it. America? Russia? As if.” He seems to consider himself a kind of socialist but hates Tony Blair and was clearly charmed by Margaret Thatcher. His descriptions of meeting her, are some of the funniest in the collection.

If you’re interested in books about espionage and national security, don’t miss the brand new Cover Stories Podcast with co-hosts Suzanne Kelly and Bill Harlow.

His later letters seem to show a world view not really distinctive from that of any other subscriber to the New York Times or the Guardian. He goes berserk over Brexit, gets an Irish passport (a form of anti-Brexit virtue signalling) and writes that Britain is “in the hands of far-right Trumpists”. He decides the US that elected Donald Trump in 2016, must be a “rogue state” and describes Edward Snowden as a great American; he struggles with his reception in the US as with no other country.

This collection of letters makes no revelations about le Carre’s brief career as a spy for MI5 and MI6; but brief as it was, you can see how it marked him. On the one hand, he publicly falls out with a former MI6 Chief, Sir Richard Dearlove, tarred as a supposed accomplice of Tony Blair over Iraq. Elsewhere, he says the spy agencies in Britain have got too big for their boots, and tells a former BND chief that “in a healthy democracy, it is probably not desirable that the intelligence services be wholly efficient, or wholly admired” (many will agree on that point). At the same time, he keeps in touch with former MI6 colleagues; he greets the fall of the Berlin Wall as almost a personal triumph; and in his last months, he writes mysteriously that MI5 and MI6 “are the only places, apart from writing”. We also learn that he was distressed by falling out, in his seventies, with an old left-wing friend on whom he had reported to MI5; his reasons for doing so were, ultimately, rejected along with le Carre’s friendship.

Le Carre was a lively and compassionate correspondent. He does not pretend to have lived the life of a saint, and faces up to the ways in which he has hurt people, professionally and personally. “I just wanted to improve my game, and since you can’t disown success, having trodden over bodies to get it, I tried to enjoy it, too” he writes, perhaps disarmingly, in 1992.

There’s lots of humour in his letters, too. South African friends will forgive me for enjoying his remark about a “telephone interview with a woman in South Africa who likes to keep her radio programmes light-hearted. If I lived in South Africa, so would I”.

Cipher Brief readers will enjoy this book, despite some of his comments on the US.

For much of my life, I have been both irritated and entertained by le Carre’s books, and for me – as for others of my generation, or older – his legacy will be the novels he wrote during the Cold War, or it will be nothing. But I did not expect that reading these letters would bring deeper appreciation of le Carre’s honesty and humanity. Life is full of surprises.

A Private Spy earns a prestigious four out of four trench coats.

Disclaimer – The Cipher Brief participates in the Amazon Affiliate program and may make a small commission from purchases made via links

Read more expert national security perspectives and analysis in The Cipher Brief