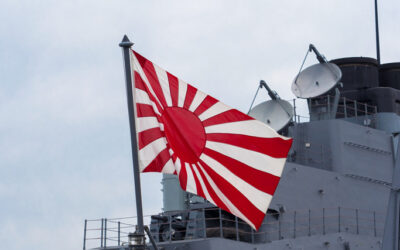

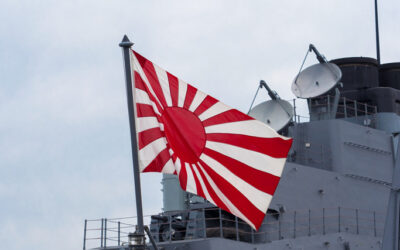

What Japan’s Massive Defense Investment Means for the World

BOTTOM LINE UP FRONT: Japan’s new security strategy is bringing unprecedented change to its military policy and is introducing a new dynamic for global collective […] More

Three decades ago, The Blue Ribbon Commission on Defense Management (colloquially known as the Packard Commission after its Chairman David Packard) published A Quest for Excellence, its seminal study of the Department of Defense’s (DoD) organization and management processes. Commenting on DoD acquisition procedures, the Commission concluded that “the nation’s defense programs lose far more to inefficient procedures than to fraud and dishonesty. The truly costly problems are those of overcomplicated organization and rigid procedure…” Two decades earlier, in 1970, the Fitzhugh Commission determined that the problem in defense acquisition is that “everyone is responsible for everything and no one is response for anything.”

Today, those diagnoses remain perceptive and the remedy prescribed by the Packard Commission equally prescient: “…it is possible to make major improvements in defense acquisition by emulating the model of the most successful industrial companies.”

Although considerable progress has been made in improving DoD acquisition processes—and encouraging bipartisan efforts are ongoing today—there are still lessons the Department can learn from the private sector. One such area is the acquisition of information technology (IT).

The breakneck pace of IT innovation has precipitated a fundamental shift over the last five to seven years in the private sector’s requirements and acquisition processes. The traditional longer, more expensive requirements processes have become untenable; and yet, an organization’s capacity to efficiently acquire IT and adapt to innovation is increasingly fundamental in today’s operating environment. As a result, we are seeing fewer “big bang” acquisitions of large encompassing platforms and systems.

Instead, companies are starting small – conducting iterative evaluations in real-time, and adjusting as needed. Advances in cloud computing and scale-out architectures have enabled companies to do several proof of concepts and purchase IT hardware as they need it, rather than investing in an expensive system in advance.

Granted, this may be a challenge for a large organization such as DoD, which has much more scale and a lower risk threshold. But even large businesses are shifting toward more transformed acquisition processes as they try to adapt at a pace similar to their disruptive competitors.

Importantly, this smaller scale approach not only allows an organization to adopt innovative technology more quickly, it also helps to address and mitigate risk up front. Traditional requirements processes are intended to mitigate risk by conducting long-term studies, contracting with consultants, and ensuring all options are reviewed in advance of the decision. An agile approach, however, allows companies to start small, avoid making large up-front investments, obtain a quick read on the most recent implementation, and scale up as appropriate. Keeping the initial investment small helps to reduce the overall risk and largely obviates the need for longer requirements processes.

In fact, inherent in traditional long-term requirements processes is the risk that the solution an organization seeks to acquire will be the wrong fit for the market once they access it. Indeed, this is a new type of risk that private sector companies are factoring in. Nowhere is this truer than in cyberspace, where the pace of innovation changes the environment on a seemingly monthly basis. Even a two-year acquisition process will almost guarantee that the solution will be outdated by the time it is realized. In such a dynamic space, requirements processes should account for an organization’s current needs and be able to adapt to an inevitable change in the market space.

One way to accommodate the pace of innovation is through open architecture. No longer can companies acquire large systems by planning into the future to the “nth” degree, because by the time that future arrives, the inputs will have changed, new inputs will have been developed, and the competitive and market space will be different. Open architecture allows an organization to build a system that is suited for today’s issues and adaptable to tomorrow’s changes. It provides increased interoperability, modularity, and the ability to incorporate new technologies as appropriate without overhauling an entire system.

Financial and business realities also challenge the traditional long-term horizon of acquisition processes. Whereas, four decades ago, shareholders held a share of stock for an average of eight years, today that average is four months—and declining. This implies that a firm’s owners—including those firms supporting national defense—have little interest in what happens to the firm 10 or 15 years from now. The emphasis is increasingly on the near-term.

As such, it is important that DoD understands the technical and business forces affecting traditional acquisition processes and identifies those best practices that may be adopted within the Department. In acquiring information technology, the private sector has mitigated risk and benefitted from the rapid pace of innovation, all while achieving shorter time horizons. It also leverages open architectures to accommodate the undefined, but inevitable changes that will take place in the market and in technology.

Further, whether acquiring information technology or other goods and services, improvement begins with instituting effective personnel management systems—ones that delegate authority to employees, reward success, and contain failure. In the private sector, competent, dedicated, and experienced people are entrusted with the freedom to exercise judgement and are evaluated accordingly. If we are to tackle longstanding challenges and make the acquisition process reflect private industry, we must first make the personnel management system more business-like. That is, they must be granted both discretion and accountability.

Indeed, the challenges identified by the Packard Commission 30 years ago and the Fitzhugh Commission 50 years ago persist today, and there is no silver bullet for addressing them. But if there is anything approaching a silver bullet, it is to use, wherever possible, the proven methodologies inherent in America’s private sector. That is the prescription recommended decades ago, and that is what continues to be the most viable and proven way to continue our quest for acquisition excellence.

Related Articles

BOTTOM LINE UP FRONT: Japan’s new security strategy is bringing unprecedented change to its military policy and is introducing a new dynamic for global collective […] More

EXPERT PERSPECTIVE – Following recent Russian airstrikes on Kyiv, Germany sent the first of four planned IRIS-T SLM air defense systems to Ukraine. France, the […] More

EXPERT PERSPECTIVE – Russian authorities say they shot down a Ukrainian drone over the area that serves as headquarters for the Russian Black Sea Fleet […] More

EXPERT PERSPECTIVE: The presence of drones/UAV’s in armed conflicts as varied as Syria, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Ukraine is not only influencing military tactics and strategy but it’s […] More

According to a recent report by the National Defense Strategy Commission (NDS), the U.S. Department of Defense and the White House “have not yet articulated […] More

As tensions heat up between Russia and the West, cold-war skills are back in play. Norway and Iceland are hosting more than 50,000 troops from […] More

Search