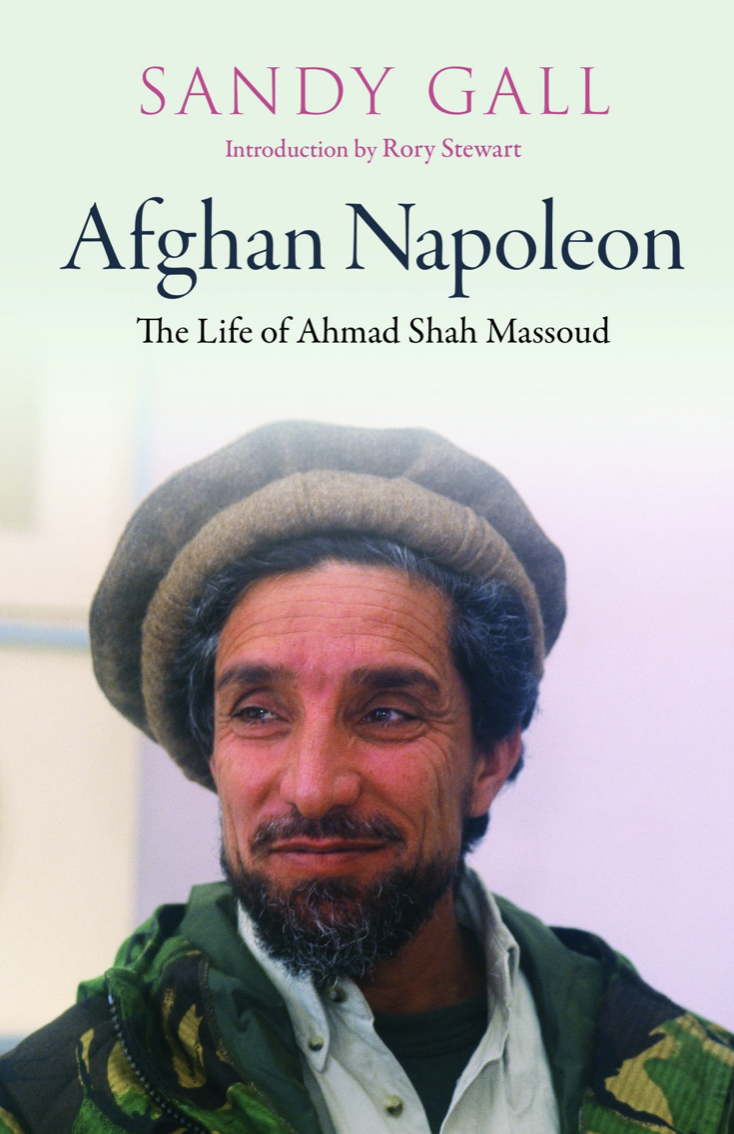

Afghanistan’s Napoleon and how things could have been different

BOOK REVIEW: Afghan Napoleon: The Life of Ahmad Shah Massoud

By Sandy Gall / Haus Publishing

Reviewed by Tim Willasey-Wilsey

The Reviewer — Tim Willasey-Wilsey served for over 27 years in the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office. He is now Visiting Professor of War Studies at King’s College, London. His late career was spent in Asia including a posting to Pakistan in the mid 1990s.

REVIEW — Sandy Gall’s biography of Ahmad Shah Massoud, Afghan Napoleon, arrived at bookshops just as the humiliating events of August 2021 had unfolded. It was Massoud’s assassination by Al Qa’ida just two days before 9/11 which deprived Afghanistan of its most skilful military commander. What, one wonders, would have happened if NATO had had an Afghan strategist of his calibre to work with during these past 20 years?

One thing is for sure; with Massoud it would have been a more genuine partnership. He would never have tolerated the dominance which Western powers exercised in Kabul nor the humiliating dependency and rampant corruption which dogged the Afghan central and provincial governments. Whether Massoud would ever have been acceptable to Pakistan or indeed to the majority of Pashtuns is another matter. Pakistan always saw him as a Tajik whereas Massoud regarded himself as an Afghan above all else.

First however, we should celebrate Sandy Gall’s achievement. This book, written at the age of 94, is undoubtedly the best of his several works on Afghanistan. His various treks into Soviet-occupied Afghanistan were both arduous and courageous and later led to some wonderful work supporting wounded Afghans with purpose-made artificial limbs from a base in Peshawar. Typically, Sandy makes no mention of his charity work. Furthermore, his timing is impeccable as we all sift through the charred wreckage of our long Afghan involvement and try to understand what went so badly wrong.

Then there is Massoud himself. Those of us who have been immersed in Afghanistan thought we knew Massoud as a brilliant tactician but also as a warlord; certainly a less cynical warlord that Rashid Dostum, Abdul-Rasul Sayyaf and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar but a warlord nonetheless. Many Afghans, particularly, the residents of Kabul blame Massoud and Hekmatyar equally for the appalling shelling of the city in 1992 and 1993. I spent some time in Kabul in 1993 and have no doubt that the vast majority of the shells and rockets which landed in the city came from Hekmatyar’s forces camped outside the city at Charasyab. The Gurkha guards at the British Embassy compound would pick up the munitions debris every morning by the barrow load; all had come from the direction of Charasyab. However, Massoud also had innocent blood on his hands. In 20 years as a mujahideen commander that was inevitable.

Excerpts from Massoud’s own diaries, included with the permission of the family, reveal him to be a deeply reflective and humble man. Many of his observations reveal a remarkable degree of introspection and occasionally self-doubt, mixed with religious devotion and a love of Afghan poetry. He also tended to analyse his successes and failures as well as drawing up annual reviews of his achievements, failings and objectives. It has to be admitted that these show a greater degree of self-awareness, realism and objectivity than similar documents produced for and by Western military commanders and ambassadors about the situation in Afghanistan. However, Massoud was writing to himself; he had nobody else to impress or persuade.

The Cipher Brief hosts expert-level briefings on national security issues for Subscriber+Members that help provide context around today’s national security issues and what they mean for business. Upgrade your status to Subscriber+ today.

Massoud is often criticised, particularly in Pakistan, for his truce with the Soviets in 1983. However, Gall draws upon a variety of sources, to demonstrate that he made use of the truce to prepare his forces for the next onslaught as well as to extend his reach across northern Afghanistan. His critics like to suggest that Massoud had a cosy deal with Moscow. Nothing could be further from the truth. The Soviets launched attack after attack up the Panjshir Valley with ever increasing force including Hind helicopters, SU-27 ground-attack aircraft and GRU Spetsnaz. The burnt out BTR and BRDM armoured vehicles, some of which still litter the terrain, are testimony to Massoud’s brilliant defensive tactics and to the near-impregnability of the valley itself.

The book’s title is taken from the instructions of a senior MI6 officer in 1980 to one of his subordinates to “go out and find someone among the Afghan mujahideen….of the calibre of the young Napoleon”. MI6 found Massoud whereas the Americans and Saudis were pointed by Pakistani intelligence (the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate-ISI) towards the Pashtun leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Furthermore, the Americans and Saudis sent all their finance and munitions through an agreed ISI-controlled channel whereas MI6 enjoyed a degree of independence.

Gall regrets the United States’ choice because Hekmatyar proved to be a psychopathic killer. The then Saudi intelligence chief, Prince Turki al Faisal’s recent book on Afghanistan (The Afghanistan File, Arabian Publishing 2021) similarly rues his involvement with both Hekmatyar and with ISI because of their political and diplomatic inflexibility. And yet Gall quotes the same senior MI6 officer as acknowledging that the Americans were right to support Hekmatyar “because he and his allies were the strongest force” (p.227). After all the CIA’s sole aim was the defeat of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan.

There are a few omissions from the narrative. Sandy makes no mention of the negotiations with the CIA to try and capture Osama Bin Laden (OBL) back in 1999 (see for example page 493 of Ghost Wars by Steve Coll. Penguin Press, New York. 2004). There is little about Massoud’s relationship with the French which was possibly as extensive as his link to MI6. There is nothing at all about Indian support, which later guaranteed Pakistani hostility to him. Above all there is remarkably little about Berhanuddin Rabbani and the nature of Massoud’s relationship with the man who should have been (but perhaps was not) the political counterweight to Massoud’s military prowess.

Sandy is critical of the West’s abandonment of Afghanistan once the Soviets had departed. I remember well being briefed in London in 1992 that we were no longer interested in Afghanistan. Pakistan with its militant groups, its nuclear ambitions, its atavistic hatred for India and an insurgency in Kashmir was now the bigger worry. It is a regrettable reality that countries have only limited political bandwidth and finite funding for matters of immediate concern.

The detailed description of how Massoud’s assassins were finally granted their interview makes for agonising reading. It seems that almost everyone was suspicious of the two men and their wafer-thin cover stories. Massoud had also been disconcerted by intelligence reports that Al Qa’ida was planning “something big” against the Northern Alliance (p.280-1) And yet he too did not join the dots. He was always willing to give press interviews, partly because of his geographic isolation in the Panjshir Valley.

Finally, there are moments of painful irony. Gall quotes the Soviet Colonel Khabarov “I still feel guilty and bitter about the Afghan government forces…. we betrayed and sold down the river when we departed from Afghanistan, leaving them and their families at the mercy of the victors” (p.115). How many of us share that very same sentiment three decades later?

Afghan Napoleon is awarded a solid three out of four trenchcoats

Read Under/Cover interviews with authors and publishers in The Cipher Brief

Interested in submitting a book review? Check out our guidelines here

Sign up for our free Undercover newsletter to make sure you stay on top of all of the new releases and expert reviews

Disclaimer – The Cipher Brief participates in the Amazon Affiliate program and may make a small commission from purchases made via links.

Read more expert national security perspectives and analysis in The Cipher Brief

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business.