After Israel’s Retaliation Against Iran, What Comes Next?

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — For nearly a week, the Middle East and much of the world were on a knife’s edge, waiting for a promised […] More

In Part I of this Opinion Series on Innovation, I explained How the Intelligence Community Kills Ideas and specifically illustrated how IC bureaucracy crushed employee ‘Mark’s’ idea. As a result of the response, Mark suffered an ABC trifecta of social pain (I’ll explain that below). The rejection violated his sense of autonomy, the snubbing assaulted his sense of belonging, and the ambiguity of the process ravaged any sense of certainty. That’s why it’s highly likely Mark will fail to come up with any significant new ideas in the future.

In part 2, we’re considering IC manager Fred, who thinks that employee Roz is troublesome because she:

Fred is correct.

But what Fred doesn’t know is that his boss thinks the same is true of him.

These four bullet points hold for all employees and managers in the IC because they describe universal aspects of human nature.

How Good are IC Employees?

I worked for Jack Welch at General Electric during the company’s heyday in the 1990s. At its peak, GE appeared on the cover of almost every business magazine each month. Some of these articles declared GE had the best workforce in the world.

I compared my direct experience with GE employees with my decades of experience with IC employees. In my opinion, the IC workforce today is even better than the GE employees of the 1990s. The reason for this extraordinarily high-quality IC workforce is the effectiveness of its selection process, including polygraphs, one-on-one interviews, medical exams, and a battery of high-validity psychology assessments. On the one hand, the selection process is highly inefficient and time-consuming, primarily because of the security subprocess. Still, on the other hand, it is highly effective in selecting good employees and screening out bad ones.

The personal values held by the IC workforce support my high opinion of them. Here is how a poll that included more than 900 IC employees, ranked the respondents personal values:

In my opinion, IC employees have far fewer issues and shortcomings than any other workforce on earth. And yet despite their admirable values, people are affected by their environment—people learn quickly what they need to know in order to succeed in a long-term career. For instance, IC employees are high achievers and that produces a culture of competition. If the competition is healthy and constructive, it works well, but in situations where employees work for bad managers, new ideas are threatening and competitiveness can become destructive.

As one operational psychologist commented:

“From my perspective, IC employees are high achievers, low in straightforwardness, low in trust of others, conflict-avoidant, competitive, interpersonally savvy, and sometimes manipulative. These are necessary skills in an isolated, large, highly competitive bureaucracy where most people stay for 25-30 years.”

In short, IC employees are selected well, but affected positively and negatively by their environment, and, of course, all too human.

The Cipher Brief hosts expert-level briefings on national security issues for Subscriber+Members that help provide context around today’s national security issues and what they mean for business. Upgrade your status to Subscriber+ today.

Examining Human Flaws

Let’s start with my tongue-in-cheek definition:

Human nature is marked by psychological fear, over-sensitivity, and a craving to belong. It fabricates wild stories to define reality and in the face of uncertainty, it digs in its heels.

We’ll examine these human foibles in the following three sections:

It’s crucial to understand these three subjects because a lot of wheel-spinning occurs when executives choose to ignore human nature or the “soft stuff.”

As discussed in Part I, our survival instinct causes us to run from threats and toward rewards. But keep in mind that fear is more potent than reward. For example, visualize yourself standing in an orchard picking a delicious apple. Suddenly, you hear rustling at your feet. What do you do? Still pick the apple (reward) or jump away from a possible venomous snake (fear)?

In the modern workplace, the unconscious instinct for survival reveals itself more in psychological and social survival than physical survival. For example, psychological fear explains the failure of early 2000s pay-for-performance efforts in both the IC and the Department of Defense (DoD).

The concept of higher pay looked good on paper—it assumed people will work harder if given more money—but hidden employee fears overwhelmed the attraction of reward. Employees were concerned over possible unfairness, the kludged mechanical assessment process to determine pay levels, and wary of bosses’ abilities to fairly judge. The proposal sparked an uproar. A flood of employee complaints and letters to Congress finally caused the misguided efforts of both the IC and DoD to collapse.

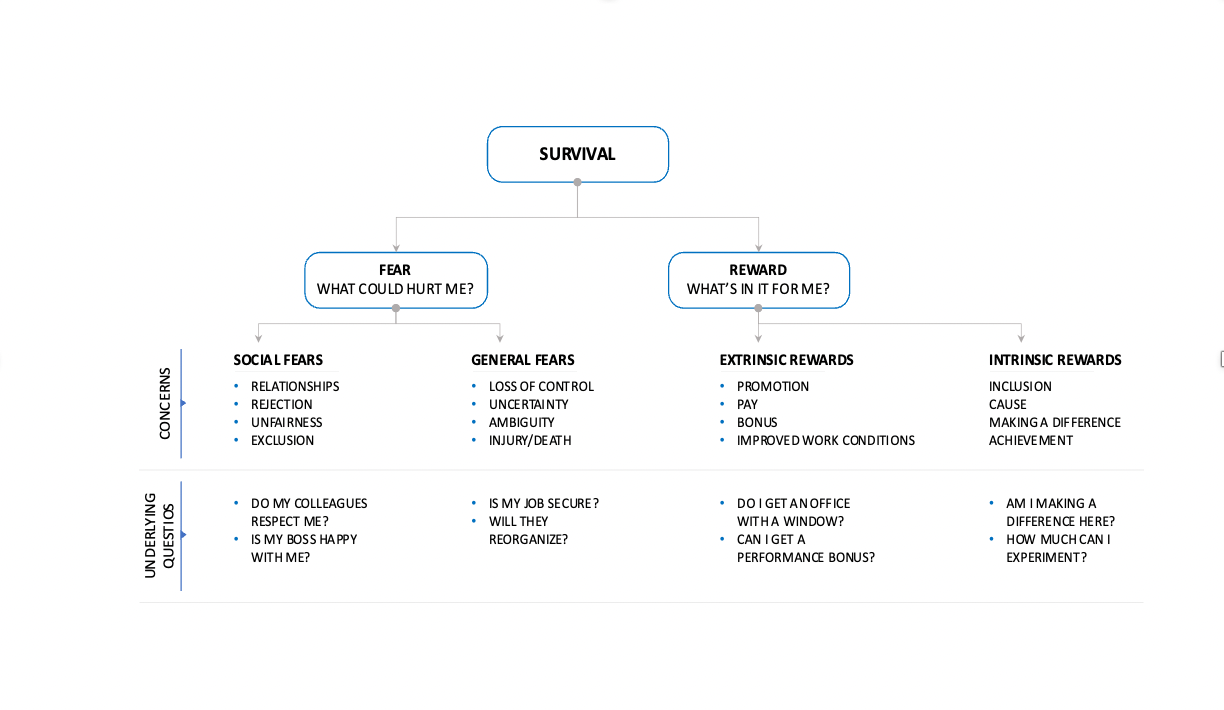

In today’s workplace, psychological and social fear are often expressed as anxiety, much of which is generated by the health of our relationships with each other. Experts have shown that bonding is a primary human drive. Bonding is evolutionarily based, critical for survival, and as Gallup has proven through tens of thousands of workplace surveys relationships with colleagues and bosses are critical to us. Let’s look at how this plays out in the schematic below.

The workplace questions listed in the bottom row include Do my colleagues respect me? and Is my boss happy with me? These questions are crucial to all of us, including Roz—she lugs those questions around in her mind but is afraid to raise them with her boss, Fred, for fear of looking silly.

Inside and outside the IC, that unconscious survival instinct perches inside a nest of employees’ unspoken psychological and relationship concerns, taking shape as some of the following questions:

Why did the pay-for-performance debacle occur? Despite a dedicated website, frequent lengthy emails, numerous speeches, and breakout sessions, none of the information addressed unconscious employee fears. What does this mean for me? How will this be administered? They’re messing with my pay!

Gap Filling

Because your mind wants you to survive, the human mind abhors uncertainty—danger lurks in uncertainty. Since I don’t know what lies in that swamp, I’m not going to wade through it.

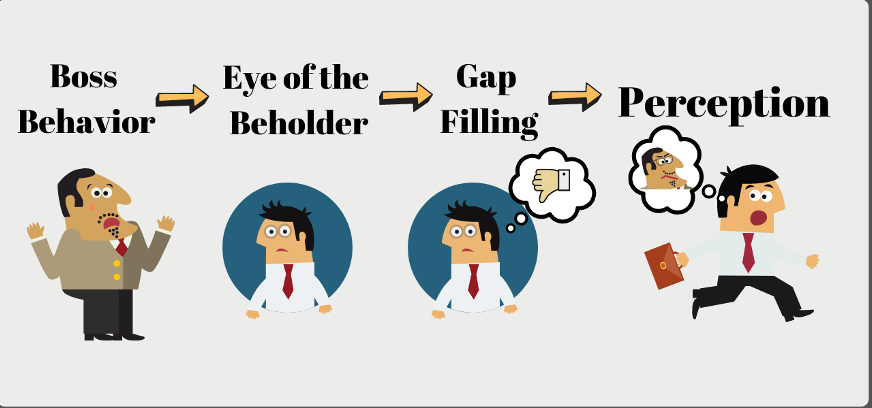

The mind is limited in the number of inputs it can take in. As a result, certainty is elusive. To reduce uncertainty, the mind fills in what it doesn’t know. Going back to our introduction, Fred thinks Roz misinterprets what she should, whereas Roz thinks she’s clear on her tasks. Fred and Roz carry two different views of reality.

Psychologists call this gap-filling process a “narrative.” An example is my dislike for my workmate, Jennifer. I saw her dash away from the copier as I approached. When I tried to use it, I discovered it was out of paper. Jennifer rushed off without filling it! My narrative is that Jennifer is selfish, a slacker, not a team player, and someone you can’t trust.

Then, with these initial perceptions, I expanded my narrative to include Jennifer’s lack of intellect. Not knowing she graduated much higher in her college class then I did, should anyone ask, I’ll tell them Jennifer is as dumb as a teenage squirrel.

I made up this narrative because I lacked input. In reality, Jennifer had a meeting with her boss in one minute and discovered the empty copier. Almost late for her appointment, she rushed off.

Here’s another example of gap filling—one I’m not proud of. As I walked through CIA headquarters, I spotted a former employee, Mark. He told me that things were going great—he had just received a coaching certification from Georgetown. When I congratulated him, he appeared puzzled.

He responded, “I thought you hated coaching.”

Taken aback, I asked, “Why?”

He answered, “Ten years ago, I came to your office to see if I could get coaching training, and you winced.”

Two narratives are at play here. Mark saw his dream go up in smoke when I grimaced. In his mind, my gesture meant I hated coaching. On the other hand, the story in my head was that Mark’s group was lagging in designing an SIS (Senior Intelligence Service) training program. My boss, a stickler for details and deadlines, pressured me for results, so I felt squeezed. I remember Mark’s visit to my office, but I don’t recall wincing.

Here is the Mark vs. Mike infographic.

Each time employees observe a boss’s behavior, they consciously or unconsciously tag it with a descriptor. They see a behavior, create a reason for it, and label their boss as having a certain attribute. That attribute is often negative—it is safer to assume that the rustling in the orchard is a snake, even though it is probably only a chipmunk.

The ABCs of Bad Managers

Studies show that bad bosses elicit lower employee performance. The pain from having a lousy boss is similar to the pain from when you were picked last for dodgeball. It’s intense.

One SIS officer told me, “I worked for a particularly awful person in a very senior position. That person was a screamer and routinely demeaned people in front of others. It was a nightmare, and the only thing that got me through it was protecting the people under me.”

Intense emotional pain overwhelmed that SIS officer. She stopped coaching and energizing her employees, instead falling into a defensive mode of protecting them.

At UCLA and the University of Colorado, neuroscientists have labeled this sharp emotional pain “social pain.” Their experiments show that social pain is held onto longer and more intensely in the brain than physical pain. As an example, you remember someone who betrayed you in high school more than the physical pain from spraining an ankle.

Mark was correct. I did wince during our session ten years earlier. How do I know? Even though I don’t remember it, Mark recalls it vividly because I destroyed his coaching dream and it caused him social pain.

Social pain erupts from an ABC of occurrences that violate our sense of autonomy, belonging, or certainty:

This simple ABC model explains why those unconscious workplace questions listed at the bottom of the survival schematic above are vital. For example, Autonomy: Is my boss happy with me? Belonging: Do my colleagues respect me? Certainty: Is my job secure?

When a significant number of IC bosses fail to answer these nagging, conscious and unconscious employee questions or build an abundance of safety and trust with employees, IC performance will lag.

In Closing

If we apply industrial-age management practices in the IC workplace, human survival instincts, gap filling, and our irrational reaction to social pain, management becomes extremely difficult. Good spies need to understand what makes people tick—shouldn’t the managers of those spies know the same? It would be better for Roz if Fred led with human nature instead of constantly pushing against it.

All Roz and any of us want is to have a little respect, be listened to, have a tiny piece of the pie, engage in meaningful work, and have clarity on how we are doing. When those needs are met, great things happen.

In Part III, we’ll cover simple management techniques that bypass humankind’s shortcomings and allow human greatness to blossom.

After graduating from West Point and Harvard Business School, Mike Mears founded and ran the CIA’s Leadership Academy before retiring as the CIA’s Chief of HR (Human Capital). He is an international leadership consultant and is writing a book titled Changing Minds—Brain-Friendly Ways Great Bosses Energize Employees and Change Culture.

Read more expert-driven national security insights, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief because National Security is Everyone’s Business.

Related Articles

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — For nearly a week, the Middle East and much of the world were on a knife’s edge, waiting for a promised […] More

BOTTOM LINE UP FRONT – Less than one week after Iran’s attack against Israel, Israel struck Iran early on Friday, hitting a military air base […] More

SUBSCRIBER+EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW — While Ukraine deals with shortages of troops, munitions, and equipment for its air defenses, some Ukrainians are teaming up with foreign investors […] More

SUBSCRIBER+EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW — With a mere 1.2 million citizens, Estonia is among NATO’s smallest members, but its contributions to Ukraine have led the pack by […] More

SUBSCRIBER+EXCLUSIVE BRIEFING — Drone weapons are part of the daily narrative of the war in Ukraine – from Russia’s use of Iranian drones against infrastructure […] More

SUBSCRIBER+ EXCLUSIVE ANALYSIS — Iran’s retaliatory strikes against Israel this weekend were both a potentially game-changing, historic first — and an underwhelming response. Historic, because […] More

Search