Ignore the Threat of Russian Intelligence Operations at Your Own Peril

SUBSCRIBER+EXCLUSIVE EXPERT PERSPECTIVE / OPINION — The Russian Intelligence Services are getting a lot of attention in the U.S. media these days. It makes sense. […] More

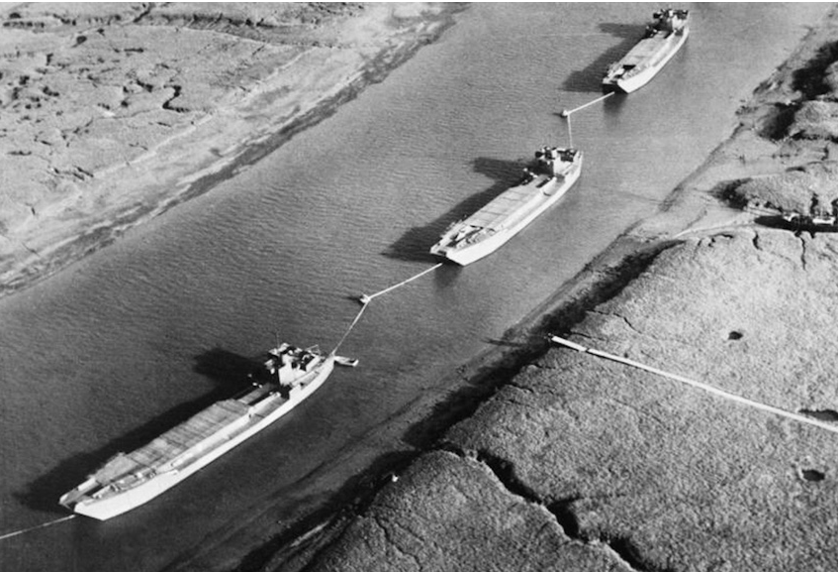

(Photo caption: Full-size dummy LCTs, codenamed BIGBOB, moored in South East England before the Normandy invasion (British Imperial War Museums, photograph H 42527, public domain).

This article was adapted from a nonfiction postscript in Christopher Turner’s Lieutenant Barnaby’s Inflatable Air Force.

Christopher Turner had a 25-year career in the Central Intelligence Agency’s Directorate of Operations, during which he completed several sensitive assignments in the Far East, South Asia, and Europe. Prior to his government service, Turner worked as an archaeologist in the US, Polynesia, and Southeast Asia. He is the author of the nonfiction book, The CASSIA Spy Ring: A History of OSS’s Maier-Messner Group, the historical espionage thriller Where Vultures Gather, Lieutenant Barnaby’s Inflatable Air Force, and the forthcoming Sunset in the Garden of Eden, a parable set in the physical and moral extremes of the Second World War.

Attack him where he is unprepared; appear where you are not expected.

These military devices, leading to victory, must not be divulged beforehand.

—Sun Tzu, The Art of War

“Democracies need to re-learn the art of deception” proclaims the title of a recent article in The Economist. To make its case, the article begins with a rundown on some of the brilliant military ruses that, during the Second World War, were part of the Allies’ deception strategy, codenamed BODYGUARD. The article’s contention—with which I agree—is that, while deception operations are not the answer to every intelligence question, for certain objectives they are peerless.

The article includes contemporary examples of successful deception operations and techniques, some of which were drawn from recent activities by the West’s adversaries—Russian predations in Crimea and Chinese development of unsettling new battlefield-ready devices. In the West, the article concludes, the art has been mostly lost. To rectify this sad state of affairs, historical case studies should be scrutinized, their methods should be revived and modernized, and they should inspire innovation.

But not everyone is a fan of the dark arts. “There’s a cultural problem here,” a CIA officer tells The Economist. “I do think you’ll find [US] generals who would feel that it’s fundamentally not a very respectable activity.” This observation, if true, smacks of the gullibility of former US Secretary of State Stinson, who in his memoirs famously justified his 1929 decision to shut down the US’s “Black Chamber,” a national cryptanalysis organization: “Gentlemen don’t read each other’s mail.” Less than a decade after Stinson’s withdrawal of life’s-blood funding for the Black Chamber, the world would be dragged, country by country, into the largest conflagration in history. To save lives, to conserve matériel, and to gain advantage, the arcane arts and sciences of signals intelligence would need to be reinvented, sometimes from scratch.

Now, we have the opportunity to follow a better path: We can learn from and be roused by historical precedent. We can, as the saying goes, hit the ground running.

On the subject of military deception, few examples from the past encapsulate more lessons than does Operation FORTITUDE, a key element of BODYGUARD that was designed to obfuscate Allied plans and intentions before the landings at Normandy. To accomplish this lofty goal, the operation’s intricacies sought to mislead Germany about the invasion’s time and place, and about the personnel and equipment that would be committed to the endeavor.

FORTITUDE, which was split into two elements, NORTH and SOUTH, fed the Germans abundant and varied intelligence to suggest that the Allies were marshaling large forces and vast matériel for invasions of the Norwegian coast and France’s Pas-de-Calais. To substantiate this assertion, FORTITUDE NORTH conjured the British Fourth Army in Scotland, a fictive menace poised to ply the North Sea and to secure a foothold in Scandinavia, and FORTITUDE SOUTH contrived the First US Army Group (FUSAG) in South East England, an imaginary force prepared to vault across the Dover Strait, the Channel’s narrowest point.

To enhance the legend of FUSAG, Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight Eisenhower appointed US Army General George Patton as the group’s commander. (British MI5 officer Christopher Harmer, a key player in the deception plans, was credited with first suggesting that Patton should lead FUSAG.) The Allies knew that the Wehrmacht regarded Patton as being a fierce and capable leader, the sort who would likely spearhead the invasion. Hitler, who shared his military’s opinion, once declared, “[Patton is] their best general.”

The task of refining German ideas about FUSAG’s leadership fell to Britain’s top double agents, spies who were fully trusted by Germany but who in fact were controlled by Britain. General Omar Bradley, whose command of the First US Army also placed him at the helm of FUSAG, was in the thick of real D-Day preparations and had to be distanced from the FORTITUDE SOUTH deception. With careful coordination, double agents BRUTUS (Roman Czerniawski) and GARBO (Juan Pujol García) clarified to their German handlers in May 1944 that Patton had been appointed as FUSAG’s commander for the invasion, replacing Bradley’s largely titular role during the group’s formative stages. (As of late April 1944, the Germans believed that Bradley was FUSAG commander and that the First US Army and Ninth US Army were subordinate to FUSAG.) The result was that, to German eyes, FUSAG evolved over time into a hefty, purpose-built unit for the invasion—with bellicose, six-gun-toting Patton at the reins. For good measure, to put physical distance between the two generals, GARBO also reported that Patton’s FUSAG headquarters was somewhere near Ascot, some 92 miles (148 kilometers) east of Bradley’s in Bristol. (FUSAG’s notional headquarters was in Wentworth Estates, about five miles east of Ascot.)

But for all of the substance that this intelligence appeared to convey, in reality FUSAG was little more than an organizational chart that detailed how such a military unit would be structured, staffed, administered, and deployed. To flesh out the branching diagram beneath Patton’s name, the Allies used “special means”—a codified set of methodologies that created the impression of genuine activities and entities.

FORTITUDE SOUTH invoked sundry special means: staged movements of high-profile personnel to simulate the typical activities of FUSAG’s command staff; coordinated handling of double agents; complementary exploitation of ULTRA signals intelligence (i.e., decrypted German secret transmissions); fabricated radio communications to support the ruse that military units were stationed at Dover and were spoiling for a fight; IBM machine-generated blocks of random words, which Allied Morse Code operators transmitted to simulate encoded messages; deceptive lighting to suggest round-the-clock activities at specific locations; prudent release of disinformation (often in the form of devised diplomatic “leaks” that could be collected by the Germans); and false-front military facilities and full-size dummy equipment, to include tanks, airplanes, and landing craft.

To these special means were added military actions that appeared to confirm Allied intentions. For example, the balance of the pre-invasion RAF/USAAF bombing campaign—the softening of coastal defenses and disabling of logistical linchpins—tilted toward Pas-de-Calais. Normandy remained a target, as the Germans presumed it would. After all, the Allies would not concentrate all of their aerial firepower on, and thereby risk highlighting, their main objective.

FORTITUDE SOUTH’s special means were orchestrated to provide putative corroboration to the Germans. For example, General Patton was photographed on visits to fake facilities, meeting with presumptive FUSAG soldiers. To add another dimension to this activity, a (controlled) German agent might report on American troops in the same vicinity, providing an estimate of the units’ armor. And then, in the event that aerial reconnaissance or undetected spies inspected the location, a formation of (inflatable) M4 Sherman tanks and a string of moored (tube and canvas) 160-foot LCTs (Landing Craft, Tank) would visible.

In the Abwehr, German Military Intelligence, instances of apparent corroboration created a false sense of security and seem to have lowered the level of counter-intelligence scrutiny to which collected information was subjected. Also, courtesy of FORTITUDE’s ministrations, the Germans were flooded with intelligence on myriad topics, all of keen interest and begging for urgent attention. Double agent GARBO alone submitted 500 verbose reports in the five months before D-Day. Such a heavy volume of ostensibly high-grade information would have increased the time and effort that the Abwehr devoted to processing, analyzing, and disseminating reports, and may have further reduced their wherewithal to conduct due diligence. As the concept runs, in a downpour one will have great difficulty spotting a misshapen drop. (Also involved in processing information from these sources was Fremde Heere West, the intelligence-analysis unit of the German High Command.)

From these bits of altered and fabricated intelligence, the Germans stitched together their order of battle. This was perhaps BODYGUARD’s most brilliant accomplishment. If the Allies had tried to leak a more cohesive picture of the D-Day deception, no matter how cleverly they had devised its passage, as a whole or as a series, the Reich would’ve smelled a rat. But by having the Germans codify intelligence from myriad sources, work out the supposed convergence of disparate lines of reporting, and develop analytical conclusions about what the data were implying about plans for the invasion, the Allies induced the enemy to think that it had stumbled upon the war’s biggest secret.

Once the intelligence verdict was handed down, the oblivious Wehrmacht wasted no time in taking action. Renowned General Field Marshal Irwin Rommel worked tirelessly to reinforce the Atlantic Wall, the network of western coastal defenses that stretched from Southern Europe to Scandinavia. With limited resources and time, Rommel drew on intelligence estimates for deciding where and how to construct new defenses and to strengthen existing ones. Much of his attention was devoted to Pas-de-Calais, in response to the growing certitude that the main Allied invasion force would land there—although, to his credit as a worthy opponent, Rommel continued to cast a wary eye on the beaches of Normandy.

In the end, FORTITUDE SOUTH was a resounding success. The deception was so convincing that, for several weeks after D-Day, as many as 22 divisions of the German Army held their defensive posture at Pas-de-Calais, surmising that the Allied offensive at Normandy was a feint designed to draw the Wehrmacht away from the real target. Allied double agents lent credence to this supposition, in that they continued to report that, despite the landings at Normandy, FUSAG remained in South East England, straining at the leash for the imminent assault on Pas-de-Calais. Though these agents were merely reading from an Allied script, the Germans were never the wiser. The Wehrmacht’s delay in redeploying every available asset to meet the attack at Normandy contributed to the Allies’ success in securing a series of beachheads and advancing decisively inland.

In retrospect, some of the special means may have been overkill. While the Germans glimpsed a few fake landing craft in the distance, they never saw any of the other mock-ups. After the Luftwaffe’s drubbing in the Baby Blitz during the first four months of 1944, it was unable to conduct meaningful reconnaissance over Britain. Still, the decoys served other important purposes—as props and backstory for visits of military dignitaries, and for indemnity in case British security services had failed to net all of the enemy spies working in their country. (In fact, MI5 had apprehended every German spy in Britain. The British Double-Cross System was predicated on the assumption—backed by ULTRA decrypts—that MI5 had complete control of German espionage activities in the country.)

The incomparable lessons of FORTITUDE were not immediately forgotten. Some Cold War deception practices traced their origins back to the special means used in the months before D-Day. On occasion, cognizant of Soviet satellite and aerial reconnaissance, the USAF tethered inflatable F-16 Falcon jet fighters to its bases’ aprons. The dummies’ purposes were two: to misinform the USSR about F-16 deployments and numbers, and to draw enemy fire away from the real fighters. These USAF decoys were so realistic that high-resolution cameras—whether overhead or on the ground—were probably unable to discern them from nearby genuine aircraft.

Today, in a world filled with asymmetrical actions against elusive targets, but with the lingering possibility of more conventional operations in select flashpoints, FORTITUDE’s brand of deception has largely lost favor. But its value remains unchanged by fickle opinion. We would be well served to scrutinize the peerless work of FORTITUDE’s masters, picking and choosing what might still be useful, and seeking inspiration among those yellowed pages and tattered photographs for solutions to our new problems.

Further Recommended Reading

Roger Hesketh, Fortitude: The D-Day Deception Campaign (New York: The Overlook Press, 2000).

Thaddeus Holt, The Deceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., 2010).

Ben MacIntyre, Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies (New York: Broadway Books, 2012).

The Cipher Brief may earn a small commission from books purchased via these links.

Read more expert-driven national security insight, perspective and analysis in The Cipher Brief

Related Articles

SUBSCRIBER+EXCLUSIVE EXPERT PERSPECTIVE / OPINION — The Russian Intelligence Services are getting a lot of attention in the U.S. media these days. It makes sense. […] More

SUBSCRIBER+EXCLUSIVE REPORTING — The nation’s top intelligence agencies delivered a sobering threat assessment Monday, focused on spillover dangers posed by the wars in Ukraine and […] More

CIPHER BRIEF REPORTING – A retired Air Force Intelligence Officer turned whistleblower testified before a House Oversight Committee on Wednesday that the U.S. government is not […] More

EXCLUSIVE SUBSCRIBER+MEMBER INTERVIEW — Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin says there is “no such thing as an overseas police station” but U.S. counterintelligence officials beg […] More

Subscriber+Exclusive Interview — In his new book, By All Means Available: Memoirs of a Life in Intelligence, Special Operations, and Strategy, former Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence […] More

SUBSCRIBER+EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW — A provision of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act that has generated controversy around fears of the potential for abuse has proven to be crucial […] More

Search